‘The Most Resilient New Yorkers’ — Oysters Get Second Life in Harbor

See shells journey from dinner plates to docks as environmentalists and restaurateurs use mollusks to boost local ecology.

By Samantha Maldonado

Photos by Ben Fractenberg

December 1, 2022

On your plate, the gray meat of an oyster is usually nestled into a palm-sized, pearlescent shell, waiting to be eaten.

But around New York City, the bivalves cling to concrete and one another, all while working to make the harbor a stronger, healthier place.

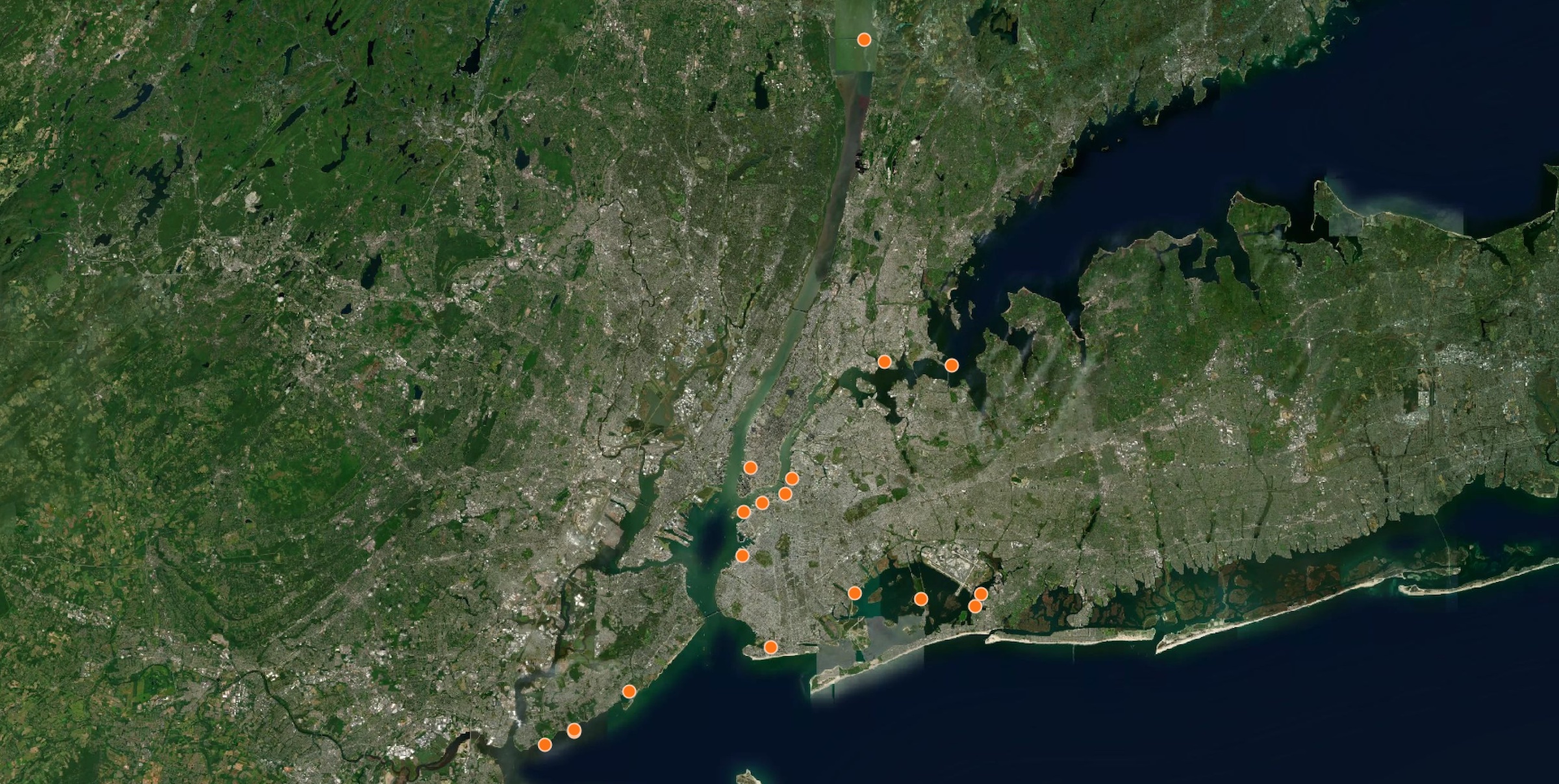

Founded in 2014 with a goal to reintroduce oysters — a billion of them — into the New York Harbor by 2035, the Billion Oyster Project is about giving spent oyster shells a second life. BOP has in eight years restored about 120 million oysters, but the project works towards a target of installing 100 million oysters per year starting in 2024. The City Council Committee on Resiliency and Waterfronts will on Thursday hold an oversight hearing on the BOP’s efforts.

Oyster restoration is a journey that begins beyond the boundaries of the state, passing through local restaurants, with a year-long rest at Governors Island, and into the waters surrounding the five boroughs. The process harkens back to the city’s history — when oysters played a major role in the local economy and culture — and looks to build a more hopeful future.

The Billion Oyster Project is one of several oyster restoration projects across the country, but it’s the only one that takes place in such a busy, urbanized waterway. The ultimate goal of BOP is to return to a self-sustaining oyster population — while connecting millions of New Yorkers with the water.

“Oysters are just so much more than for your consumption. They clean the water, they provide habitat for other marine species, they are lessening that wave energy so that hopefully the storm that’s coming isn’t going to flood your basement,” said Jennifer Zhu, the BOP’s marine habitat resource specialist. “The way they can still live with trash and sewage and the dredging — it’s amazing. They are the most resilient New Yorkers that are out there.”

Sixty restaurants in Manhattan and Brooklyn participate in the Billion Oyster Project’s shell collection program, including Lighthouse BK in Williamsburg. Saving the leftover shells from the oysters that diners slurp provides the literal foundation for the oysters.

Lighthouse sources its oysters from the east coast and, as part of a suite of the restaurant’s sustainability efforts, for nearly eight years has been instructing staff to set aside discarded shells for the BOP.

“The world seems to be in a dire place,” said co-owner Naama Tamir. “We’re kind of taking a step back and shifting our systems a little bit and then putting some energy into correcting the damage.”

Pictured: Lighthouse cook Kenley Philias shucks an East Coast oyster for happy hour.

Williamsburg residents Jen Collins and Ralph Louis enjoy oysters with their happy-hour drinks at Lighthouse. Collins is friends with Tamir and knew what would become of her discarded oyster shells.

“I got to eat delicious oysters and help the environment? Great!” said Collins, who works in sales at a mezcal company.

When customers finish their oysters, Lighthouse staff put the discarded shells into special blue bins. Joel Rosado, left, and Boris Delgado, workers with shell collection partner the Lobster Place, pick up and pour the discarded shells into the back of their truck.

They made visits to multiple restaurants starting at 5 a.m., and transported the shells to a depot in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

From the depot, the shells head to Governors Island.

At the southeastern edge of Governors Island, a truck tips the shells into a pile with countless others. The mound weighs between 400,000 and 500,000 pounds, and towers over six-feet high at its tallest point. When the breeze blows, the newer shells give off the scent of the ocean.

The shells stay in the heap for about a year in order to cure, a process that clears the shells of bacteria and pathogens. Since the restaurants source oysters from all over the world, different diseases found in other water bodies could threaten the balance of the local ecosystem if introduced.

After a year, volunteers and BOP staff rinse and tumble the shells to separate any that have clumped together. They pour the shells into plastic trays, mesh bags and metal cages called gabions.

From there it’s time for “seeding” the oyster shells with larvae. The gabions make their way to the Red Hook Terminal, where they enter water-sealed shipping containers. There, water from the harbor fills the containers and staff add millions of oyster larvae to the mix. Most of the larvae comes from a hatchery in Maine.

Photo Courtesy of Billion Oyster Project

The larvae can take up to a week to attach to the shells. In some cases, larvae are seeded directly onto a ball or blocky shapes made of a special concrete. Once the baby oysters are visible to the human eye, they can go into the harbor as part of a reef.

Photo Courtesy of Billion Oyster Project

Johnny Anderson, BOP’s fabrication coordinator, pilots the boat carrying shells from Governors Island to the Williamsburg shoreline on an oyster reef installation day.

The BOP’s Emily Roan, a remote setting technician, and Zhu tag shells before placing them along the Williamsburg waterfront under part of a promenade at Domino Park — about a mile from Lighthouse.

In shallow, calm waters, BOP staff and volunteers can layer rocks, cured shells and the shells onto which the larvae have attached. But most of the New York Harbor is busy, so to make sure the shells remain in place, the oysters are installed within the metal crates, mesh bags, and other structures that hold them in place.

Pictured: Ben LoGuidice, a remote setting manager, prepares the installation of concrete disks protruding from a Williamsburg shore wall to attract marine life.

In rare cases, staff have dumped oysters directly into the water — like in the five-acre reef in Soundview, in The Bronx. But having specific structures allows staff to pull them up and move them if needed or to take a closer look as part of fall and spring monitoring.

Zhu will measure the water quality as well as the growth and mortality rates of the shellfish. Live oysters are heavier, and their shells clam up when poked. Dead oysters may have shells that are cracked open or packed with sediment. A bubble may come out when tapped.

During the monitoring sessions, BOP staff may also get a gander at wild oysters, like at Coney Island Creek and Brooklyn Bridge Park.

“We can’t say for sure if those wild oysters are the babies that are produced from our oysters or the oysters that are just out and about and already there,” Zhu said.

Pictured: Roan places bags of shells along the seawall.

Pictured: Helene Hetrick, BOP’s director of communications, scrambles over a rock wall after climbing out from beneath the Williamsburg promenade off Grand Street.

On a recent Wednesday in November, Shinara Sunderlal, an education outreach manager with BOP, hoisted up a reef structure from the water on the northeastern shore of Governors Island. She encouraged a group of second-graders from PS 676 in Red Hook to explore clumps of oysters. The oysters were between about 2 and 7 years old, with the oldest as big as the children’s faces. Some oysters grew beyond the structure meant to contain them, but Sunderlal said if they’re coming out of their cage, then they’re doing just fine.

Sunderlal pointed out burnt orange tunicates and mussels, two forms of marine life that make a home on or near the oysters, which grow in clusters and allow critters to live within the nooks. In the past, staff and students have observed clam worms, seahorses, toadfish, blue crabs and schools of bunker fish, which serve as food for humpback whales.

Marine life is an obvious sign of one of the oyster’s many benefits.

Oysters are a keystone species, which means they are a foundational part of an ecosystem on which multiple components depend.

“That keeps the ecosystem together, so if you take it away, the ecosystem collapses. When you bring it back, you are building back that whole ecosystem,” Sunderlal said.

Oysters used to thrive in the New York harbor and were plentiful. Long ago, the Lenape people ate oysters and fashioned tools from the shells. For centuries after the city was founded, oysters remained an iconic local delicacy, peddled from carts on streets and from oyster houses, like the two pictured here under the Manhattan Bridge in 1937.

But over time, the reefs became too toxic to serve as a source of food. The oyster population dropped with declining water quality — thanks in large part to industrial pollution, dredging and the combined sewer overflow system that pours raw sewage in the water when it rains— as well as overharvesting.

Photo Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Archive

The bivalves clean the water by eating microscopic, organic material like phytoplankton and zooplankton, and filtering contaminants from the raw sewage dumped into the water when the sewers — which handle both stormwater and wastewater — overflow during rainstorms. Each oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day — meaning a billion could filter the entire harbor in three days, Zhu said.

Thanks to the Clean Water Act of 1972, which began to regulate water pollution, the quality of the waters in the harbor has improved drastically over the years. But it’s still not high enough for New Yorkers to be able to eat the oysters that live in the harbor — a risk of the restoration project.

And because of smarter, environmentally friendly practices around our harbor, it’s hard to distinguish how much of the improvements in water quality and marine life can be attributed to the oysters directly, Zhu admitted.

“We’re using these oysters as a way to understand there are more natural solutions to cleaning our waterways,” she said.

Oyster reefs along the coasts also help buffer storms and shore erosion by acting as speed bumps to slow waves as they break.

“Putting in oysters is so much cheaper than putting in a wall or levee,” said Meredith Comi, NY/NJ Baykeeper’s director of the coastal restoration program, which has restored nine million oysters between the two states and collaborated with BOP in the past. “Natural systems, it’s just kind of a no-brainer. It’s gonna be protection. It’s going to restore the ecosystem. You’re going to have more critters in water.”